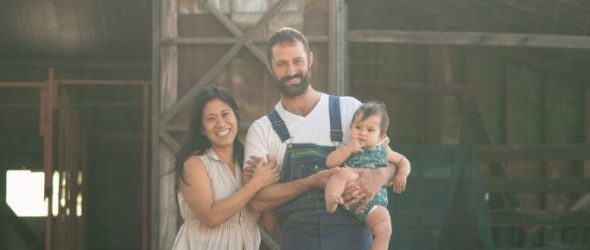

Ingrid Tsong’s family is one of several cannabis farming clans who currently call the Mayacamas Mountain Range of Mendocino home. While Tsong keeps the books and maintains compliance, her husband, Jonathan Wentzel, has been cultivating cannabis since he was a teenager.

Together, the couple run Beija Flor Farms. The name stems from the Portuguese word for hummingbird (or, more literally, “to kiss the flower”) and reflects Beija Flor’s commitment to growing the cleanest organic medicine possible. Beyond their passion for cannabis itself, they also place great importance in mitigating their contributions to climate change by employing a system of carbon sequestration on their farm.

Wentzel has been growing back since Proposition 215 put medical marijuana on the map in California in 1996. When Proposition 64 offered the pair a chance to fully legitimize their operations in 2018, they leapt at the opportunity.

“We really wanted to be in the legalized market and move forward,” Tsong explains. “We felt really excited about it but it’s been a challenge to make it work. I’m definitely an optimist at heart, but it’s been a challenge — the whole process.”

The subject of taxes may seem inherently boring to some, but for Tsong and Wentzel, changing the laws dictating the cut California takes from legalized cannabis may be the difference between whether Beija Flor stays in business or not.

At the center of the issue is what’s known as a cultivation tax, which essentially requires cannabis farmers in California to pay based on the dry weight of what they grow before it’s sold. Thus, instead of paying proportionally to sales, farms like Beija Flor must pay this tax for all the flower and leaves they grow regardless of what happens next.

According to Tsong, this can amount to 15-20 percent of the farm’s total revenue — revenue they won’t even have until the product is sold. That’s in addition to the excise tax (calculated at 15 percent of the average market price when purchased at retail), which itself has caused the cost of cannabis to dip as retailers lower prices to combat sticker shock.

“There’s basically a tax penalty to be in the cannabis business,” Tsong says, “because if you grew, say, tomatoes, you wouldn’t have to pay it.”

The other folks who don’t pay it? Those operating illegally.

The result is a vicious cycle that rewards larger, legal corporate farming operations that have the capital to withstand paying a high percentage of their potential earnings in taxes upfront without fear that diminished sales will shutter their operations. Meanwhile, illegal growers pay no taxes and are currently selling their notably less safe alternative at a fraction of the cost. In January, the United Cannabis Business Association reported that unlicensed storefront and delivery programs in the state outnumbered their legal counterparts by a ratio of nearly three to one.

At least one state legislator appears to be hearing what small farmers are saying.

In late January, Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Alameda) introduced AB 1948. If successful, the bill would eliminate cultivation taxes for three years and lower the state excise tax from 15 percent to 11 percent for the same period. A hearing on Monday, March 9 brought a number of farmers to Sacramento to voice their approval for the legislation, but their work is currently on hold as the world turns its attention fully to combating the spread of coronavirus.

Regardless, the dire need expressed by farmers to amend how cannabis taxes are collected in California is not one that can wait very long.

“We find ourselves coming close to shutting down every year,” admits Daniel Stein, who owns and runs Humboldt’s Briceland Forest Farm with his wife, Taylor.

Despite winning a prestigious 2017 Emerald Cup award for their regenerative farming practices, Briceland is also facing an uncertain future in the wake of California’s cannabis tax crunch. In addition to voicing his support for AB 1948, Stein also suggests that the state’s refusal to make more dispensaries available means a ton of cultivators are battling for limited shelf space.

Recently, Stein and Tsong both attended an informational event in Sacramento geared toward helping legislators better understand what being a legal craft cannabis farmer in California actually entails in 2020.

Stein reports that many of the individuals he spoke with were receptive, if still more than slightly confused about how everything works.

“Many of the people who are making the rules don’t understand the on-the-ground realities of this profession,” Stein says, “and that requires engagement. I understand that it’s very hard for the government to give up money that they’re already getting, especially when it was significantly less than what they expected, but that fact alone should be making them ask some hard questions about whether this is working.”