Many consider indoor cannabis cultivation to produce the highest quality cannabis available, but it’s usually thought to come at a high environmental cost. In a recently published paper, Energy Use by the Indoor Cannabis Industry: Inconvenient Truths for Producers, Consumers, and Policymakers, authors Evan Mills, PhD, and Scott Zeramby share big concerns about the energy impacts of indoor cannabis cultivation.

In the paper, they question the ethical integrity of indoor cultivation, and say that, even with improvements in efficiency, “Indoor cultivation does not appear to be defensible on energy and environmental grounds.”

Instead they point to outdoor cultivation as the most technologically elegant, sustainable, ethical, and economically viable approach for minimizing the rising energy and environmental burden of cannabis production.

But is indoor cannabis cultivation really that bad?

Energy costs for indoor cannabis

One of the main reasons Mills and Zeramby give for forgoing indoor cultivation is its extremely high energy costs. Mills studied this back in 2012, finding that indoor cannabis consumed 20 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, with additional amounts from direct fuel use, together corresponding to a whopping 15 million metric tonnes of CO2 released into the atmosphere each year—the equivalent of what you would get powering more than 2.5 million homes for a year.

Estimates back in 2012 suggested indoor cannabis growing made up 3% of California’s total electricity use and 1% of the electricity used nationally. In Denver, Colorado, the numbers were as high as 4% of the state’s total electricity usage. This was significantly more than other commercial sectors, and more than four times higher than the entire US pharmaceutical industry.

Mills and Zeramby point out that this amount of energy could power two million homes or three million cars. “From a consumer vantage point,” the authors explain, “the energy use for growing one 1-gram ‘joint’ creates 10 pounds of carbon dioxide pollution.” This is equivalent to the pollution you’d create from driving 11.3 miles in a car.

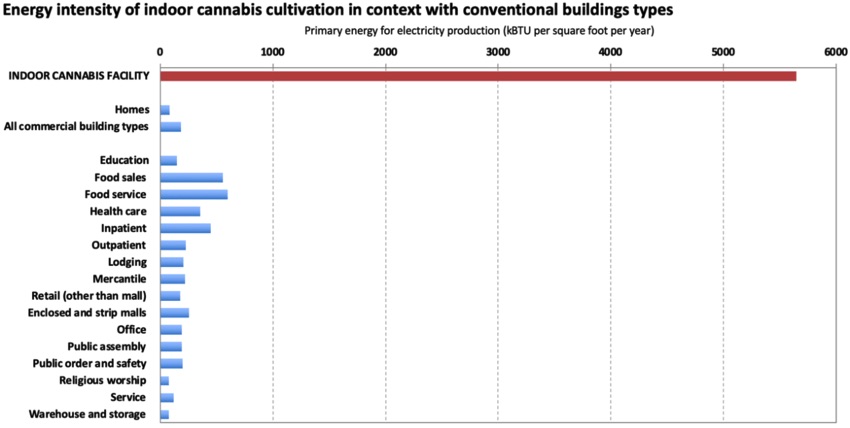

Indoor cannabis facility energy usage compared to other building types in 2012. (Figure 2 of Cannabis energy intensity from Mills (2012). Reference data from U.S. Energy Information Administration.)

Does indoor require less water?

Mills and Zeramby also point out that conventional wisdom states indoor growing is worse than outdoor for energy issues but better in terms of water usage. In outdoor growing, more water is used in watering plants. But this discounts water used in producing electricity.

They explain that the water “steadily evaporated from dams and cooling towers while producing the electricity destined for indoor cultivation facilities vastly exceeds the direct agricultural water needed to grow outdoors.”

Given this research, there is little question that the conventional methods of indoor cultivation come with a huge carbon footprint and a big environmental burden.

Why do we cultivate indoors?

Since the environmental costs are so high, why do we continue to grow indoors?

For one, it is often considered to be a higher quality than outdoor or greenhouse cannabis, getting top dollar at dispensaries. But Mills and Zeramby explain that cultivators also often prefer it for security, to keep the high-value crop indoors.

An indoor environment also protects plants from unpredictable weather and other crop hazards, leading to a more predictable product. Additionally, indoor growing can maximize profits by requiring fewer employees, allows for year-round growing in any climate, and multiple harvests per year.

But perhaps the biggest reason for indoor cultivation is the way cannabis has been regulated. Historically, the illegality of cannabis forced growers into hiding their cultivation operations indoors, with blacked out windows, powerful lights, and high-powered filters and air-conditioning units to keep things cool and keep odors from escaping and raising suspicion.

While cannabis legalization in some areas has led to improvements, there are still regulatory challenges that keep cultivation indoors. Unlike other agricultural products, which are usually grown openly in a climate they are best suited for and then shipped to other areas, restrictions around cannabis transportation and sales mean that each state, or sometimes country, needs to produce their own cannabis.

In the US, states like California have a good climate for outdoor growing, but many states, counties, and countries either don’t have the right climate for outdoor cannabis cultivation or are required to grow indoors due to zoning and land use issues. Some requirements may make outdoor growing nearly impossible, such as in areas where the only properties zoned for cannabis are in urban spaces.

Additionally, in some areas, outdoor growing is entirely banned. “There’s a lot of restrictions because of fears of odor complaints and things like that,” said Neil Kolwey, an expert in industrial energy efficiency. So many areas are currently dependent on indoor cultivation to supply their cannabis markets.

To add to this, Mills and Zeramby point out that in some areas, “‘Financial incentives’ for energy

efficiency is offered to indoor growers by utility companies,” making it more cost effective than outdoor growing and inadvertently driving up the environmental cost of cannabis production.

“Cannabis policy and environmental policy must be harmonized. Until then, some of the nation’s hardest-earned progress towards climate change solutions is at risk as regulators continue to ignore this industry’s mushrooming carbon footprint,” said Mills and Zeramby.

Solutions to cannabis energy problems

Mills and Zeramby argue that policymakers need to address this energy problem but have been mostly silent. A few states like Massachusetts and Illinois have taken some steps toward reducing their own cannabis industry’s energy footprint by requiring cultivators to use more energy-efficient technology, and California is currently considering mandating that indoor cultivators use LEDs instead of energy-hogging HPS lights.

But the authors point to policies that would encourage outdoor growing, as they don’t believe indoor growing can ever become sustainable. Others, while agreeing that outdoor is environmentally better, point to ways to make indoor growing more efficient.

Kolwey, who produced a report on how growers can reduce their environmental impact, found that by adopting more efficient methods of lighting, cooling, and dehumidification, growers can reduce energy use by as much as 32%. He believes that when cannabis becomes legal at a national level, large operations will overtake small ones, saying “From an environmental point of view, that’s okay, because the larger ones are gonna be more efficient.”

He also points to efforts to certify environmentally friendly indoor grows, with the hopes that consumers will be willing to support them. He also recommends switching to LEDs, while Mills and Zeramby argue that LEDs don’t do much to lessen energy costs.

Noah Miller, CEO at LED company Black Dog LED, said, “Many years ago, we proved that our lights allow for a 60% reduction in HVAC use due to our unique spectrum. That was with much less efficient LED technology.” He argues that “with the efficiency we can attain now, along with the HVAC cost reduction, I would say any study showing LED doesn’t significantly reduce the energy footprint of a cultivation facility is outdated.”

Nishant Reddy, Co-Founder and CEO of Northern California producers A Golden State, said that his company maintains carbon neutrality by using LEDs, using snowmelt for water that is so pure it requires less filtration (and thus less energy), growing in a climate that doesn’t require much cooling or heating, and funding projects to offset their carbon footprint, “including planting small community trees in India, Kenya, and Uganda, preventing deforestation at a rosewood forest preservation in Brazil, and providing cookstoves for impoverished communities in Honduras,” he said.

New technologies are also being developed to make indoor cannabis more energy-efficient. SunVentive Zero, for example, sells a system that brings natural sunlight into indoor settings without the added heat you’d find in greenhouses. Early research on the technology in a small test grow showed energy reductions by 87-90%, and the company is currently testing the technology on larger canopies.

While the average indoor grow may be taking a big toll on the environment, new solutions exist to offer hope that technological advancement, policy change, and consumer pressure, could make it a more sustainable option. It already is sustainable for some.

Until more growers follow suit and become more sustainable or regulatiations shift, it is up to consumers to decide whether they want to continue to support these high energy practices or go with companies that use more sustainable ones.