But Dr Juliet Gerrard says whether that would come to pass if the country voted to legalise recreational cannabis is unknown.

“We’re pretty sure of the situation at the moment. We’re much less sure of what will happen if we legalise it,” Gerrard told the Herald.

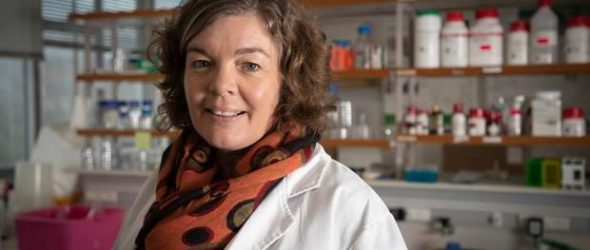

Gerrard has led an expert panel of academics, researchers and health and social experts – co-chaired by Auckland University Professor Tracey McIntosh – in gathering information to inform the debate in the lead up to September’s vote.

The panel’s work, peer-reviewed internationally and nationally, is going live at 11am today and contains a wealth of information.

Gerrard said the panel didn’t make any recommendations or take a position on the Cannabis Legislation and Control Bill, which would set up the regulatory framework.

It compared the proposed legal framework to the status quo, looked at what has happened overseas, and dived into the health risks, including who is most at risk: users who start young, use frequently and use potent products.

But Gerard said the panel also looked at social harms and the systemic racism in the criminalising and policing of cannabis – which could be greatly improved by legalisation.

“Instinctively when people hear the word harm, they think about the medical harm. Less well documented is the social harm – people getting kicked out of school for a drug offence, a drug conviction on a record which could affect employment prospects and cascade into a series of social harms.

“The people in that situation are disproportionately young, disproportionately male and disproportionately Māori.”

Māori are three times more likely to be arrested and convicted of a cannabis-related crime than non-Māori, and the Drug Foundation estimates that legalising cannabis could reduce Māori cannabis convictions by up to 1279 per year.

Asked how much a game-changer legalisation could be in the fight against systemic racism, Gerrard said: “Certainly the social justice experts on the panel think [the proposed legal framework] would make a big difference to those communities.”

Thousands of people are convicted of cannabis offences every year; 2238 people were charged in 2019 for possession/use.

“A large number of minor convictions would be removed,” she said.

Gerrard noted that cannabis offences would still exist in the proposed legal framework – for example, for smoking in public, advertising, or supplying or selling to someone under 20.

The social equity clause in the proposed framework could also see part of the national production cap be given to poorer communities that have come to rely on the black market for income.

“A lot of that will depend on how the [new national cannabis authority] manages the licensing,” Gerrard said.

The wrong regulatory framework could also exacerbate social inequity, she added.

“If commercial players take over, use could go up and harm could go up.

“The bill is a balance between state control and allowing business to enter the market.”

The bill includes a clause so that one business would not be able to contribute more than 20 per cent of the national supply.

Gerrard said the overseas evidence was too young to show any long-term trends, but short-term ones included a moderate increase in adult use, and little change in use patterns among heavy users or young users – the two groups most at risk.

The proposal for New Zealand is most similar to the existing framework in Canada, she said, where frequent usage has only increased for those aged 65 and over.

“The fact there hasn’t been major changes for youth use or at-risk groups is promising. The over 65s are the least at risk. The younger you start to use, the more risk.”

She said the panel didn’t look at how much money could be redirected from enforcement to health services.

But there were few such services for cannabis-related harm, and few people seek them out.

“It’s absolutely clear it’s much easier to provide health and social support for legal drugs than illegal ones.

“People are much more likely to seek help if cannabis is legal, presuming that health and social services are made available – and that could reduce harm.”

She said people often had a kneejerk reaction when thinking about the referendum.

“They think, ‘It does harm. Why would you legalise?’ But there’s plenty of harm happening at the moment.”

The key question is the harm it might do and whether that harm increases or decreases in a legalised framework compared to the status quo.

On that, Gerrard stuck to the panel’s remit and remained steadfastly silent.