Bruce Barcott and Andrew GeorgeJuly 24, 2020

Sean Worsley worked on a IED/bomb disposal unit for 14 months in Iraq. He returned home alive but wounded, and used medical marijuana to manage his brain trauma and PTSD. But now he can’t, because Alabama locked him up in prison for five years after a small-town cop found Worsley’s medicine in his car during a family road trip. (AdobeStock)

edical marijuana is now legal in 35 states. Some form of cannabis—even if just CBD—is legal in 47 states. Nationwide polls show more than 90% of Americans believe patients should have the right to use medical cannabis without fear of arrest and incarceration.

So why is Sean Worsley, a 33-year-old Iraq War veteran and Purple Heart recipient, locked up in an Alabama prison cell for five years? He’s there because of music, medical marijuana, and the racist trap known as cannabis prohibition.

He’s there because he dared to treat his PTSD—a result of his 14 months spent working with a bomb squad in a war zone—with medical marijuana and made the mistake of driving through Alabama with his medicine in the car.

Sean Worsley served his nation honorably for five years, including a 14-month deployment to Iraq. (Photo courtesy Sean & Eboni Worsley / Last Prisoner Project)

It started with a family visit

Worsley’s story began innocently enough.

Four years ago, in the summer of 2016, he and his wife Eboni were visiting her family in Mississippi. They decided to make a ten-hour drive to visit Worsley’s grandmother in North Carolina. She had been displaced by a hurricane and he was planning to help rebuild her house.

Heading east along Highway 82, the Worsleys pulled in to the Jet Pep gas station in Gordo, Alabama, a small town about 20 miles outside Tuscaloosa. It was a little past 11pm on August 15, 2016. As he pumped, music spilled out of Worsley’s car.

The loud music attracted the attention of Carl Abramo, a local Gordo cop. Abramo investigated. Why he investigated is unclear. Bumping a tune while pumping gas isn’t yet a crime in Alabama. But maybe it counts as suspicious behavior in Gordo.

According to Abramo’s later report, he “observed a Black male get out of the passenger side vehicle. They were pulled up at a pump and the Black male began playing air guitar, dancing, and shaking his head. He was laughing and joking around and looking at the driver while doing all this.”

Sean and Eboni Worsley in more recent and happier days, prior to Sean’s incarceration in Alabama. (Photo courtesy of Sean & Eboni Worsley, LPP)

Air guitaring while Black

Based on his keen observation of a man enjoying a family road trip with his wife, Officer Abramo approached Sean Worsley and requested a search of Worsley’s car.

Again: Why? This is unclear. Abramo claimed to smell marijuana, but that assertion—which is impossible to prove or disprove—has long been used by police as a false pretext to stop and harass people of color. In some medically legal states, in fact, the “smell of weed” has been disqualified as probable cause for police investigation.

Here’s a detail that matters in America: Sean Worsley, the military veteran, is Black. Carl Abramo, the small-town Alabama cop, is white.

Worsley consented to the search, believing he had nothing to hide.

In fact, he did have something to hide. Worsley is a disabled veteran with a traumatic brain injury. He uses medical cannabis to manage his PTSD and ease his back pain.

Serving on a ‘Hurt Locker’ squad

During his five-year stint in the military, Sean Worsley didn’t just bide his time. He worked one of the toughest, most dangerous jobs in the world. Worsley spent 14 months assigned to a bomb squad in Iraq, working in deadly environments similar to the ones portrayed in the Oscar-winning movie The Hurt Locker.

The job involved long stretches of boredom punctuated by terrifying missions to dismantle improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Worsley and his squad saved many lives, but they also watched fellow soldiers die in horrific explosions.

On one mission, Worsley was knocked unconscious and had to be dragged out of his vehicle to safety. That led to a traumatic brain injury, and may have exacerbated his PTSD.

Once stateside, Worsley treated his injuries and his PTSD with an ever-expanding list of pharmaceuticals prescribed by Veterans Administration doctors. Eventually he turned to medical cannabis, which is legal in his home state of Arizona, and weaned himself off the pills.

Sean Worsley and thousands of other Arizona veterans manage their health conditions with state-licensed medical marijuana, purchased in clean, modern dispensaries. Some stores, like Harvest House of Cannabis (pictured here) offer deep discounts to military veterans. (Photo courtesy of Harvest of Baseline)

One of many veterans who turn to medical marijuana

Eric Goepel, founder and CEO of the Veterans Cannabis Coalition, said Worsley’s experience is a common one among America’s wounded warriors.

“Like hundreds of thousands of veterans wounded in combat, the treatment [Worsley] received amounted to being told to consume cocktails of toxic and addictive pharmaceuticals, ranging from antipsychotics and antidepressants to opioids and stimulants, for the rest of his life,” Goepel told Leafly. “Ground down under the weight of a regimen of pills that threatened to kill him, he turned to cannabis as an alternative. Sean joins the ranks of more than 20% of the veteran community who use cannabis to manage their conditions.”

Worsley’s medical marijuana was perfectly legal in Arizona, but absolutely illegal in Alabama. Officer Abramo found Worsley’s medication in the back seat, properly labeled in a pill jar. Worsley explained that he was a disabled veteran and showed Abramo his Arizona medical marijuana card.

The cop told Worsley his card was no good in Alabama, where medical marijuana remains illegal. Abramo placed both Sean and Eboni under arrest. They were taken to the Pickens County Jail, where they languished for six days.

But that would be just the beginning of Sean Worsley’s nightmare.

Cannabis prohibition in the South

he American South has been one of the last strongholds of cannabis prohibition. In recent months, though, progress has begun to arrive. Virginia officially decriminalized marijuana and opened up its medical cannabis program last month. Louisiana has begun selling cannabis to patients in dispensaries. In November, Mississippi residents will vote on a statewide initiative to legalize medical cannabis.

But Alabama remains locked into the past century’s drug war. As Leah Nelson, research director at the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, recently explained:

“First-time possession [of marijuana] is charged as a misdemeanor if the arresting officer thinks it was for personal use; all subsequent instances of possession are felonies. If the arresting officer believes the marijuana is for ‘other than personal use,’ then possession of any amount can be charged as a felony even if it’s an individual’s first time being arrested for possession.”

In other words, the entire trajectory of a person’s life and liberty could be based on the arresting officer’s belief that the cannabis in question is or is not simply for personal use.

One cop decides a man’s fate

Despite Sean Worsley’s medical marijuana card, and his documented service in the Iraq War and struggles with PTSD, Alabama state law allowed a cop from Gordo, pop. 1,750, to depict Worsley as a drug dealer moving heavy weight with intent to sell—and not a wounded military veteran on a family vacation, using legal medical marijuana to manage his PTSD.

Abramo booked Sean Worsley for possession of marijuana for other than personal use, a felony. He also charged Worsley’s wife Eboni with the same crime, although the charges against her were later dropped.

The couple were released on bond after six days in jail. Sean and Eboni returned to their lives in the West, awaiting word on Sean’s next legal steps in Alabama.

Leah Nelson recorded what happened next:

“At the Pickens County courthouse, authorities locked Sean in a room apart from Eboni. A plea agreement was put before him. The plea deal included 5 years of probation, drug treatment, and thousands of dollars in fines and court costs.”

But Sean Worsley had no idea what kind of judicial nightmare he was signing up for.

A felony charge for medical marijuana

In an effort to complete the requirements of his plea deal, Worsley visited a Veterans Administration (VA) medical center in Arizona to get assessed for placement in drug treatment. But the VA refused to enroll him—because medical marijuana is legal in Arizona, and doctors there saw no evidence that Worsley abused the drug.

“Mr. Worsley reports smoking cannabis for medical purposes and has legal documentation to support his use and therefore does not meet criteria for a substance use disorder or meet need for substance abuse treatment,” read the report from the VA Mental Health Integrated Specialty Services.

Hampered by the drug charges hanging over them, Sean and Eboni struggled to find work. In early 2019, they applied for help from a VA program that assists homeless veterans. That summer, though, the VA notified Sean that his assistance would be cut off because Alabama had issued a fugitive warrant for his arrest. Apparently he’d missed a Pickens County court appearance—of which he hadn’t been aware—and the local DA issued the warrant.

Both Eboni Worsley, left, and Sean Worsley were arrested when an Alabama cop found a small amount of Sean’s medical marijuana in the back seat of their car. (Photo courtesy Eboni & Sean Worsley, LPP)

A traffic stop in Arizona

The struggle continued. Earlier this year, Sean Worsley was pulled over by police in Arizona on a minor traffic offense.

According to Leah Nelson’s report:

“The officers who pulled him over noticed [Worsley] was terrified. They asked him why. According to Eboni, he told them everything: about his PTSD, his traumatic brain injury, his expired [medical marijuana] card, the outstanding warrant from Alabama. The officers told him not to worry; Alabama would never extradite him over a little marijuana. It would be OK.”

But when they called Alabama, law enforcement officials there requested that Worsley be extradited back to Pickens County.

When the Arizona police broke the news, Worsley panicked. He ran. He didn’t get far—he fell, and the cops took him to jail.

Heaping debt on prisoners

Eventually Alabama state authorities transported Worsley to the deep South, at a cost of $4,345—which they charged him for.

Heaping court costs and ‘transit fees’ onto people who are already struggling to make ends meet has become a notoriously odious tactic in many states. The burden of jail debt is one that some people never overcome—and can keep many formerly incarcerated people, who have served their time, ineligible to vote. (The ACLU has done important work on this issue, warning of the revival of “debtors’ prisons” abolished nearly two centuries ago.)

After becoming re-acquainted with the Pickens County jail, Worsley walked into court to hear his fate determined by a local judge. On April 28, 2020, the judge removed his probation and sentenced him to five years in the Alabama state prison system.

Five years in prison—for driving through Alabama with a pill bottle of medical marijuana. And dancing at a gas station while Black.

Legal medicine, illegal state: Patients trapped

Sean Worsley’s story illustrates how a single cannabis arrest can derail a person’s life. It’s not just the arrest itself. It’s the way in which the arrested person becomes trapped in a justice system that too often ensnares people of color and those with lesser resources.

Sarah Gersten, executive director of the Last Prisoner Project, an advocacy organization working to free drug war victims, sees many Sean Worsleys in her work.

“We know that marijuana is not a gateway drug, but it is a gateway offense,” Gersten told Leafly. “Sean’s story is emblematic of how one simple possession charge, especially for a Black man in America, can easily get you caught up in a system that almost guarantees you will continue to reoffend.”

“Incarcerating our nation’s veterans for years-long sentences is not the solution,” she added. “Sean’s case serves as a stark reminder that without mental health resources, long-term care, and access to safe and effective medicine, those who have served this country risk bearing the brunt of an unjust system where even low-level offenders are destined to fail.”

Adding to the injustice is the sacrifice Worsley gave to his country: Years of military service that cost him his health and well-being. Worsley’s service in the Iraq War led to his PTSD and brain injury, which he treated with a medicine that’s legal in his home state. He followed all the rules. He only made one small mistake: He took his medicine with him while traveling. And now he’s doing a different kind of service: five hard years in an Alabama prison.

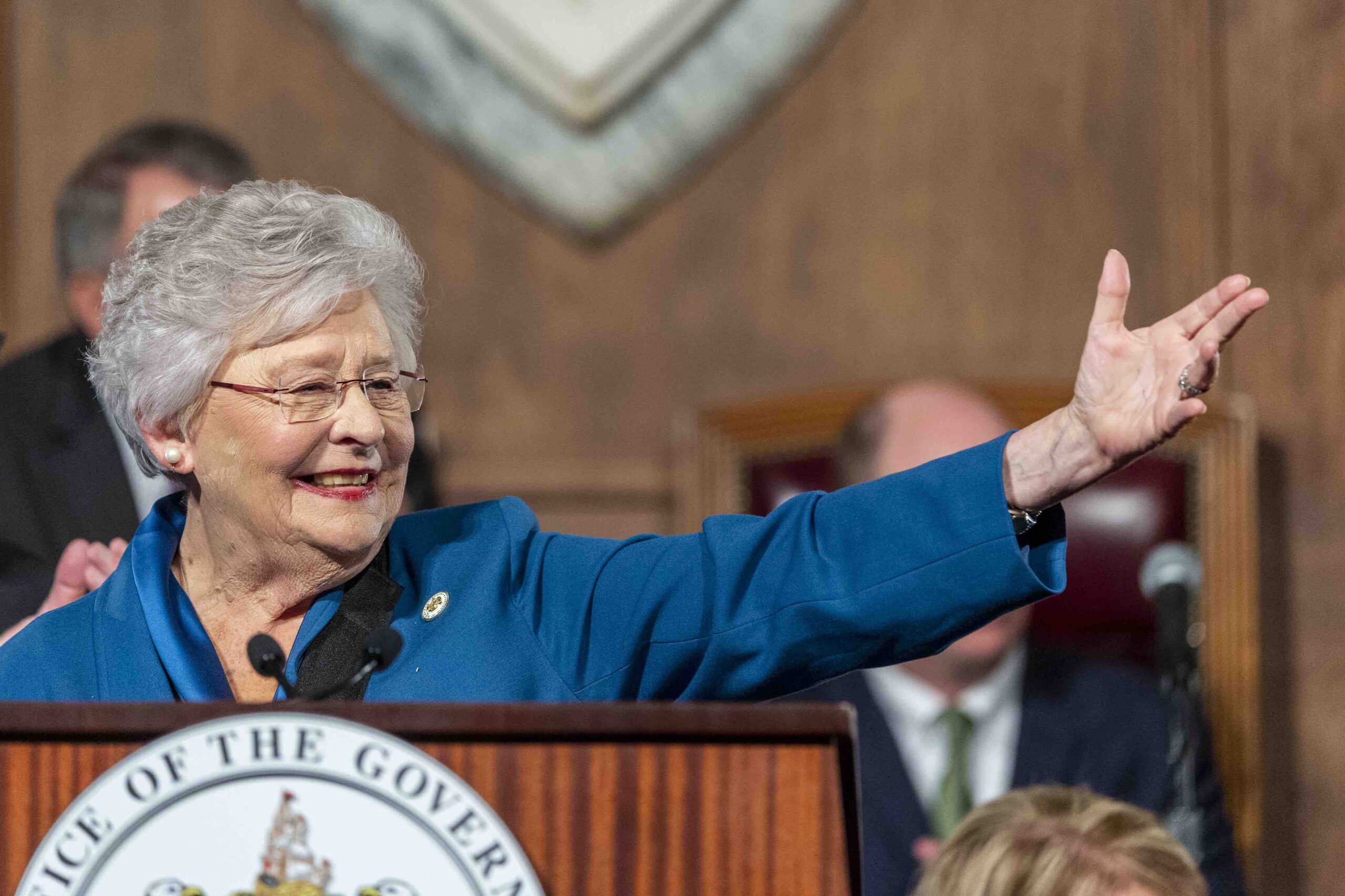

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey, seen here in February, has the power to commute Sean Worsley’s egregious sentence. Advocates are calling on her to exercise justice and mercy, and send Worsley home to his family in Arizona. (AP Photo/Vasha Hunt)

Gov. Kay Ivey can end this injustice

In a case like this, a state governor can offer appropriate justice and clemency. Alabama’s Gov. Kay Ivey is a conservative Republican, a political position that’s historically been associated with antipathy toward cannabis legalization. (Though that’s quickly changing.) But Ivey has shown an ability to maintain an open mind regarding medical marijuana.

Last year she signed Senate Bill 236, which legalized CBD oil for an extremely limited number of patients. The measure also established a committee to look into a more expansive medical marijuana program, with the intent of proposing a legalization measure appropriate for Alabama.

As more attention is drawn to Worsley’s case, the wheels of justice may begin to turn. In similar cases—most famously that of Bernard Noble, once sentenced to 13 years in a Louisiana prison for holding two joints—years of advocacy work have resulted in early release.

How you can help

You can help by:

- Donating to help Sean and Eboni Worsley with legal expenses through this GoFundMe account.

- Write words of encouragement to Sean Worsley at:

- Sean Worsley, Pickens County Jail, PO Box 226, Carrollton, AL 35447

- Learn more about Worsley and fellow drug war prisoners through the Last Prisoner Project.